Fiber-optic leap bridges African digital divide

Google committed $1 billion in 2022 to driving Africa's digital transformation, including undersea cables for faster internet connections.

Tech companies such as Google and Facebook parent Meta are investing in new data highways and speeds for Africa.

The first Google Cloud data centre on the African continent has been up and running since January in Johannesburg, South Africa.

More To Read

"The big US tech giants have recognised the existing connectivity gaps and the need for additional investment associated with this as a major business opportunity," Tevin Tafese, data scientist at the German Institute of Global and Area Studies, told DW.

"Prominent examples are Google and Meta, whose major cable projects are aimed at reducing the cost of accessing their own service in a largely untapped African market," said Tafese.

Africa undersea internet cables:

Google committed $1 billion in 2022 to driving Africa's digital transformation, including undersea cables for faster internet connections.

One of the projects is called Umoja — named after the Swahili word for unity — and aims to be the first-ever fibre-optic cable connecting Africa directly to Australia.

Anchored in Kenya, the fibre-optic cable will run through Uganda, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa, from where it will continue along the Indian Ocean bed to Australia.

Better, faster, cheaper internet

"It is expected that these projects will significantly improve internet access in Africa, speed up the connection and reduce prices," said Tafese, pointing out that reliable internet access leads to increased productivity and higher rates of employment.

Key players in African internet infrastructure include multinational telecom giants such as MTN (South Africa), Orange S.A. (France), Vodafone Group (UK) and Bharti Airtel (India).

So-called leapfrogging — when the traditional stages of technological development are bypassed in favour of more advanced solutions — has played a central role in the establishment of mobile phone use in Africa. The fixed, traditional landline networks have been leapfrogged.

"Technology has been leapfrogged," Tafese said. "All African countries, with the exception of South Africa and a few select North African countries, have gone to cellphones and mobile networks and have not used landlines and landline internet.

Leapfrogging is also taking place in the expansion of internet infrastructure when high-capacity fibre-optic cables are immediately laid instead of the copper cables that were initially used in the Global North.

Anriette Esterhuysen, an IT expert and consultant at Johannesburg's Association for Progressive Communications, told DW that she welcomes the latest developments.

"It's good that these investments are being made, that capacities are being increased and that the large technology industry is recognizing that African markets have potential," she said.

But this does nothing to change the digital inequality, which is growing even though there are more "haves" in the digital sector.

"People who have no access, no devices, no skills and no good networking are even more marginalized than before the digital boom," said Esterhuysen.

Infrastructure and accessibility can unlock digital access

Increased investment holds the promise of expanding digital engagement for more people. By bolstering infrastructure and accessibility, more Africans can tap into the benefits of the digital realm.

"It may currently make money for companies and empower the elites who are digitally enabled, but it won't really benefit wider socioeconomic development," Esterhuysen said.

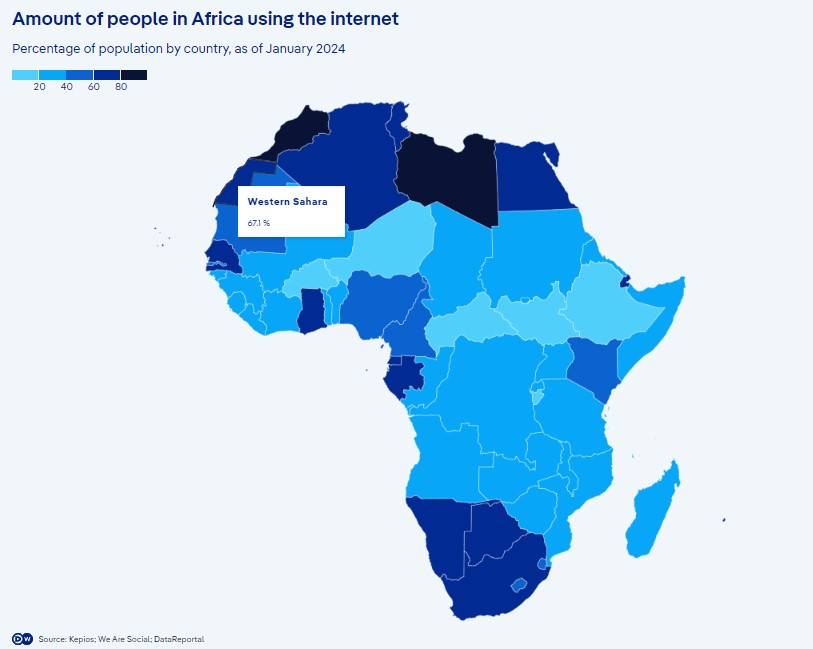

In 2024, internet usage still varies significantly across countries.

Morocco boasts 90% usage, South Africa stands at 75%, and the Central African Republic has only 11% of the population online because of infrastructure challenges and costs. Ghana, an early adopter, connected to the web in 1992.

High costs of cellphone plans widen 'digital divide'

Sub-Saharan Africa has the world's most expensive mobile data prices, which has widened the "digital divide" between internet haves and have-nots.

The United Nations Broadband Commission for Sustainable Development has set a target to bring the cost of entry-level broadband services below 2% of monthly gross national income per capita by 2025.

Achieving this goal remains elusive in many countries, and the digital divide persists.

In Ghana, for example, many people are put off by the high cost of data, said Divine Puplampu, a software developer and co-founder of Stimuluz Technologies in the capital, Accra, who suggested that the government "milks" its citizens for high cellphone fees and tariffs.

On the other side of Africa, in Mozambique, hundreds of people recently marched through the streets of downtown Maputo to the headquarters of the telecommunications regulator, INCM, to protest the country's high internet cost.

"Governments don't want to understand the importance of every citizen being empowered by the internet and therefore being able to speak their mind," said Puplampu. "Sometimes I am tempted to believe that governments are afraid of too much access to information because it could affect their power."

Africa could increasingly become a hub for digital services and work for companies in Europe and the United States, he said.

"But our government cannot guarantee a stable internet," Puplampu added, adding that officials would need to better subsidize network development.